Notes on Structure of the Atom-Class 9 Science

Atoms are the basic building blocks of matter. For a long time, scientists thought atoms could not be divided further. However, as science advanced, scientists discovered that atoms are made up of even smaller particles called subatomic particles. This chapter,” Structure of the Atom” explains what these particles are and how they are arranged inside an atom.

Here we have provided summary and revision notes for Class 9 Science Chapter 4: Structure of the Atom. These CBSE Class 9 notes are prepared in simple language. These notes help students prepare quickly and gain a clear understanding of the chapter.NCERT Solutions for Class 9 Science Chapter 4 Structure of Atom

For a better understanding of this chapter, you should also see NCERT Solutions for Class 9 Science Chapter 4 Structure of the Atom.

Discovery of Subatomic Particles

Charged Particles in Matter

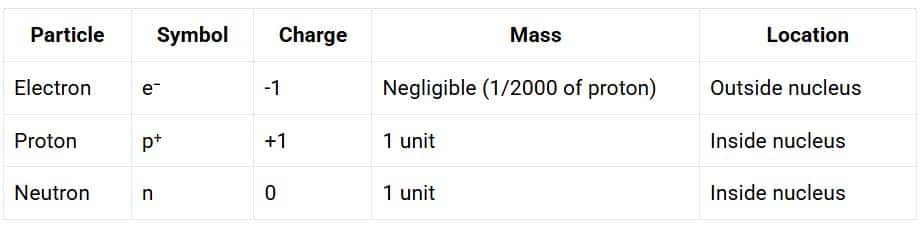

All matter contains charged particles. Subatomic particles are smaller than the atom. These are found inside atoms. The discovery of these particles helped scientists understand the structure of atoms.

When we comb dry hair, the comb attracts small pieces of paper. Similarly, rubbing a glass rod with silk creates a charge. These simple activities shows that atoms contain charged particles in them. Therefore, atoms can be divided further into particles i.e proton, electron and neutron.

Scientists discovered that atoms contain at least two types of charged particles by 1900:

- Electron: Electrons were discovered by J.J. Thomson, in his cathode ray tube experiment. He won the Nobel Prize in 1906.

- Proton: Protons were discovered by Eugen Goldstein in 1886.

- Neutron: J. Chadwick discovered presence of neutrons in the nucleus of an atom.

Electrons (e⁻)

- J.J. Thomson discovered Electrons

- An electron is represented as ‘e⁻ ’

- Electrons carry a negative charge (minus one)

- It has very little mass (almost negligible)

- We can easily remove them from atoms

Protons (p⁺)

- E. Goldstein identified these particles through canal rays in 1886

- A proton is represented as ‘p⁺’

- Protons carry a positive charge (plus one)

- Its mass was approximately 2000 times as that of the electron.

- They stay in the interior of the atom

- We cannot easily remove them from atoms

Thomson’s Model of an Atom (Plum Pudding Model)

J.J. Thomson was the first scientist to propose a model for the structure of an atom. Thomson compared his atomic model to a Christmas pudding. We can also think of it like a watermelon:

Thomson Proposed that:

- The atom consists of a positively charged sphere (like the red part of a watermelon).

- Electrons are embedded in this positive sphere (like seeds in a watermelon).

- The negative and positive charges are equal in magnitude.

- The atom as a whole remains electrically neutral.

Limitations:

- This model could not explain the results of later experiments conducted by other scientists.

Rutherford’s Model of an Atom

Ernest Rutherford wanted to know how electrons are arranged within an atom. He designed a famous experiment called the alpha-particle scattering experiment.

The Gold Foil Experiment:

Procedure:

- He selected a thin gold foil which was about 1000 atoms thick.

- Fast-moving alpha (α) particles were directed to fall on the gold foil.

- Alpha particles are doubly-charged helium ions with a mass of 4 u.

- Scientists expected small deflections because alpha particles are much heavier than protons.

Observations:

- Most of the α-particles passed straight through the gold foil.

- Some of the α-particles were deflected by small angles.

- Surprisingly, one out of every 12,000 particles appeared to rebound (deflected by 180°).

Conclusions from the Experiment:

- Most of the space inside the atom is empty.

- The positive charge of the atom occupies very little space.

- All the positive charge and mass of the atom are concentrated in a very small volume within the atom.

- Rutherford also calculated that the radius of the nucleus is about 10⁵ times less than the radius of the atom.

Features of Rutherford’s Nuclear Model:

On the basis of his experiment, Rutherford put forward the nuclear model of an atom, which had the following features:

- There is a positively charged centre in an atom called the nucleus.

- Nearly all the mass of an atom resides in the nucleus.

- The electrons revolve around the nucleus in circular paths.

- The size of the nucleus is very small compared to the size of the atom.

Drawbacks of Rutherford’s model of the atom

The revolution of the electron in a circular orbit is not expected to be stable. Any particle in a circular orbit would undergo acceleration. During acceleration, charged particles would radiate energy. Thus, the revolving electron would lose energy and finally fall into the nucleus. If this were so, the atom should be highly unstable and hence matter would not exist in the form that we know. We know that atoms are quite stable.

Bohr’s Model of Atom

Neils Bohr overcame the objections raised against Rutherford’s model.

Bohr put forward the following postulates:

- Only certain special orbits known as discrete orbits of electrons are allowed inside the atom

- While revolving in discrete orbits, the electrons do not radiate energy

These orbits or shells are called energy levels. They are represented by the letters K,L,M,N,… or the numbers, n=1,2,3,4,….

This model successfully explained the stability of atoms.

Neutrons

J. Chadwick discovered another sub-atomic particle, the neutron, in 1932.

Properties of Neutrons

- Neutrons have no charge (they are neutral).

- They have a mass nearly equal to that of a proton.

- They are represented as ‘n’.

- Neutrons are present in the nucleus of all atoms except hydrogen.

Mass of an Atom

The mass of an atom is given by the sum of the masses of protons and neutrons present in the nucleus.

Summary of Sub-Atomic Particles

Electron Distribution in Shells

Bohr and Bury suggested the distribution of electrons into different orbits of an atom. Shells or orbits are the fixed circular paths in which electrons revolve around the nucleus.

Rules for Electron Distribution

Rule 1: The maximum number of electrons present in a shell is given by the formula 2n², where ‘n’ is the orbit number or energy level index (1, 2, 3, 4, …).

Examples:

- First orbit (K-shell): n = 1

- Maximum electrons = 2 × 1² = 2

- Second orbit (L-shell): n = 2

- Maximum electrons = 2 × 2² = 8

- Third orbit (M-shell): n = 3

- Maximum electrons = 2 × 3² = 18

- Fourth orbit (N-shell): n = 4

- Maximum electrons = 2 × 4² = 32

- This pattern continues for higher shells.

Rule 2: The maximum number of electrons that can be accommodated in the outermost orbit is 8.

Rule 3: Electrons are not accommodated in a given shell unless the inner shells are filled. This means the shells are filled in a step-wise manner. We must fill the K-shell first, then the L-shell, then the M-shell, and so on.

Electronic Configuration Examples

Example 1: Helium (Atomic Number = 2)

- Total electrons = 2

- Distribution: K shell = 2

- Electronic configuration: 2

Example 2: Carbon (Atomic Number = 6)

- Total electrons = 6

- Distribution: K shell = 2, L shell = 4

- Electronic configuration: 2, 4

Example 3: Oxygen (Atomic Number = 8)

- Total electrons = 8

- Distribution: K shell = 2, L shell = 6

- Electronic configuration: 2, 6

Example 4: Sodium (Atomic Number = 11)

- Total electrons = 11

- Distribution: K shell = 2, L shell = 8, M shell = 1

- Electronic configuration: 2, 8, 1

Example 5: Sulfur (Atomic Number = 16)

- Total electrons = 16

- Distribution: K shell = 2, L shell = 8, M shell = 6

- Electronic configuration: 2, 8, 6

Valency

What are Valence Electrons?

The electrons present in the outermost shell of an atom are known as valence electrons.

The Octet Rule

From the Bohr-Bury scheme, we know that the outermost shell of an atom can accommodate a maximum of 8 electrons.

Exception: Helium has only 2 electrons in its shell (called a duplet) and is stable.

Definition of Valency

Valency is the combining capacity of an element. It is defined as:

Valency is the number of electrons gained, lost, or shared by an atom to achieve a stable configuration (usually 8 electrons in outermost shell).

Atomic Number and Mass Number

What is an atomic number?

The atomic number is the total number of protons present in the nucleus of an atom. Atomic number is denoted by the letter ‘Z’

Important Facts:

- All atoms of an element have the same atomic number (Z).

- Every element has a unique atomic number.

- In a neutral atom, Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons

- The atomic number identifies an element.

Examples of Atomic Number

- Hydrogen (H):

- Number of protons = 1

- Atomic number (Z) = 1

- Carbon (C):

- Number of protons = 6

- Atomic number (Z) = 6

- Oxygen (O):

- Number of protons = 8

- Atomic number (Z) = 8

- Sodium (Na):

- Number of protons = 11

- Atomic number (Z) = 11

Mass Number (A)

The mass number is the sum of the total number of protons and neutrons present in the nucleus of an atom.

Mass number is denoted by the letter ‘A’

Formula:

Mass Number (A) = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons

Or

A = Z + N (where N = number of neutrons)

Important Facts:

- The mass number is always a whole number

- It represents the mass of the nucleus (electrons’ mass is negligible)

- Different isotopes of the same element have different mass numbers

Finding Number of Neutrons

Formula:

Number of Neutrons = Mass Number – Atomic Number

N = A – Z

Examples of Mass Number

- Carbon:

- Number of protons = 6

- Number of neutrons = 6

- Mass number = 6 + 6 = 12 u

- Aluminium:

- Number of protons = 13

- Number of neutrons = 14

- Mass number = 13 + 14 = 27 u

- Oxygen:

- Number of protons = 8

- Number of neutrons = 8

- Mass number = 8 + 8 = 16 u

- Sulphur:

- Number of protons = 16

- Number of neutrons = 16

- Mass number = 16 + 16 = 32 u

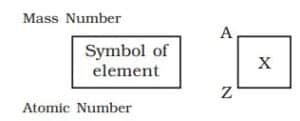

Standard Notation for Writing Atoms

Scientists use a standard notation to represent atoms. This notation shows:

- The symbol of the element

- The mass number (A)

- The atomic number (Z)

An atom is represented as follows

Where:

- A = Mass Number (top left)

- Z = Atomic Number (bottom left)

- X = Chemical symbol of element

Examples of Standard Notation

- Nitrogen:

- Symbol: N

- Atomic number: 7

- Mass number: 14

- Notation: ¹⁴₇N

- Carbon:

- Symbol: C

- Atomic number: 6

- Mass number: 12

- Notation: ¹²₆C

- Oxygen:

- Symbol: O

- Atomic number: 8

- Mass number: 16

- Notation: ¹⁶₈O

- Sodium:

- Symbol: Na

- Atomic number: 11

- Mass number: 23

- Notation: ²³₁₁Na

Isotopes

What are Isotopes?

Isotopes are atoms of the same element that have the same atomic number but different mass numbers.

Isotopes are atoms of the same element that have:

- Same atomic number (same number of protons)

- Different mass numbers (different number of neutrons)

Examples of Isotopes

Hydrogen Isotopes

Hydrogen has three atomic species or isotopes:

- Protium (¹₁H): – 1 proton, 0 neutrons, mass number = 1 (most abundant)

- Deuterium (²₁H or D): – 1 proton, 1 neutron, mass number = 2 (Also called “heavy hydrogen”)

- Tritium (³₁H or T): – 1 proton, 2 neutrons, mass number = 3(Radioactive isotope)

Carbon Isotopes

Carbon has two main isotopes:

- Carbon-12 (¹²₆C): 6 protons, 6 neutrons (most abundant, 98.9%)

- Carbon-14 (¹⁴₆C): – 6 protons, 8 neutrons (radioactive)

Chlorine Isotopes

Chlorine has two main isotopes:

- Chlorine-35 (³⁵₁₇Cl):- 17 protons, 18 neutrons

- Chlorine-37 (³⁷₁₇Cl): – 17 protons, 20 neutrons

Properties of Isotopes

- Isotopes have similar chemical properties because they have the same number of electrons.

- Isotopes have different physical properties because physical properties depend on mass. They may differ in: Density, Melting point, Boiling point, Radioactivity.

Applications of Isotopes

Isotopes have many practical uses in various fields:

- An isotope of uranium (Uranium-235) is used as a fuel in nuclear reactors.

- An isotope of cobalt (Cobalt-60) is used in the treatment of cancer.

- An isotope of iodine (Iodine-131) is used in the treatment of goitre.

- Carbon-14 is used in carbon dating to determine the age of ancient objects.

Formula for the average atomic mass of two isotopes:

\( \text{Average atomic mass} = \frac{(m_1 \times p_1) + (m_2 \times p_2)}{100} \)

where:

- \( m_1, m_2 \) = atomic masses of the two isotopes

- \( p_1, p_2 \) = percentage abundances of the two isotopes

If the abundances are given as fractions instead of percentages, then:

\( \text{Average atomic mass} = (m_1 \times f_1) + (m_2 \times f_2) \)

where \( f_1 + f_2 = 1 \)

Isobars

What is Isobars?

Isobars are atoms of different elements that have the same mass number but different atomic numbers. Or, simply

Isobars are atoms of different elements that have:

- Same mass number (same number of nucleons)

- Different atomic numbers (different number of protons)

Properties of Isobars

• Isobars are atoms of different elements.

• They have the same mass number.

• They have different atomic numbers.

• The number of protons and electrons differs in isobars.

• Their electronic configurations are different.

• Isobars occupy different positions in the periodic table.

• Their chemical properties are different.

• Their physical properties may be similar or different.

Difference Between Isobar and Isotope

| Isobar | Isotope |

|---|---|

| Isobars are atoms of different elements. | Isotopes are atoms of the same element. |

| They have different atomic numbers. | They have the same atomic number. |

| They have the same mass number. | They have different mass numbers. |

| Isobars represent different chemical elements. | Isotopes belong to one chemical element. |

| Their electronic configuration is different. | Their electronic configuration is the same. |

| The number of electrons differs. | The number of electrons is the same. |

| Isobars occupy different positions in the periodic table. | Isotopes occupy the same position in the periodic table. |

| Their chemical properties are different. | Their chemical properties are the same. |

| Isobars have the same physical properties.Example: ₆¹²C and ₅¹²B | Their physical properties are different (due to mass difference).Example: ₆¹²C and ₆¹⁴C |

Examples of Isobars

Example 1: Calcium and Argon

- Calcium (₂₀⁴⁰Ca) – 20 protons, 20 neutrons, Mass number = 40

- Argon (₁₈⁴⁰Ar) – 18 protons, 22 neutrons, Mass number = 40

- Both have mass number 40, but are different elements

Example 2: Carbon and Boron

- Carbon-12 (₆¹²C) – 6 protons, 6 neutrons, Mass number = 12

- Boron-12 (₅¹²B) – 5 protons, 7 neutrons, Mass number = 12

- Both have mass number 12, but are different elements

How to Calculate Valency

Rule 1: If valence electrons ≤ 4:

- Valency = Number of valence electrons

- The atom will tend to lose these electrons

Rule 2: If valence electrons > 4:

- Valency = 8 – Number of valence electrons

- The atom will tend to gain these electrons to complete octet

Examples of Valency

Example 1: Sodium (Na)

- Atomic number = 11

- Electron configuration: 2, 8, 1

- Valence electrons = 1

- Valency = 1 (will lose 1 electron)

Example 2: Oxygen (O)

- Atomic number = 8

- Electron configuration: 2, 6

- Valence electrons = 6

- Valency = 8 – 6 = 2 (will gain 2 electrons)

Example 3: Magnesium (Mg)

- Atomic number = 12

- Electron configuration: 2, 8, 2

- Valence electrons = 2

- Valency = 2 (will lose 2 electrons)

Example 4: Nitrogen (N)

- Atomic number = 7

- Electron configuration: 2, 5

- Valence electrons = 5

- Valency = 8 – 5 = 3 (will gain 3 electrons)

Example 5: Carbon (C)

- Atomic number = 6

- Electron configuration: 2, 4

- Valence electrons = 4

- Valency = 4 (can lose or gain 4 electrons)

Valency of Noble Gases

Noble gases (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe, Rn) have:

- 8 valence electrons (except Helium which has 2)

- Valency = 0

- They do not react with other elements because they already have stable configuration

Electronic Configuration of the First 20 Elements

| Name of Element | Atomic Number | Mass Number | Electronic Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen (H) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Helium (He) | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Lithium (Li) | 3 | 7 | 2, 1 |

| Beryllium (Be) | 4 | 9 | 2, 2 |

| Boron (B) | 5 | 11 | 2, 3 |

| Carbon (C) | 6 | 12 | 2, 4 |

| Nitrogen (N) | 7 | 14 | 2, 5 |

| Oxygen (O) | 8 | 16 | 2, 6 |

| Fluorine (F) | 9 | 19 | 2, 7 |

| Neon (Ne) | 10 | 20 | 2, 8 |

| Sodium (Na) | 11 | 23 | 2, 8, 1 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 12 | 24 | 2, 8, 2 |

| Aluminium (Al) | 13 | 27 | 2, 8, 3 |

| Silicon (Si) | 14 | 28 | 2, 8, 4 |

| Phosphorus (P) | 15 | 31 | 2, 8, 5 |

| Sulphur (S) | 16 | 32 | 2, 8, 6 |

| Chlorine (Cl) | 17 | 35 | 2, 8, 7 |

| Argon (Ar) | 18 | 40 | 2, 8, 8 |

| Potassium (K) | 19 | 39 | 2, 8, 8, 1 |

| Calcium (Ca) | 20 | 40 | 2, 8, 8, 2 |

Key Points to Remember

- Atoms consist of three subatomic particles: protons, neutrons, and electrons

- Protons and neutrons are in the nucleus; electrons are outside

- Atomic number = Number of protons

- Mass number = Protons + Neutrons

- Isotopes are atoms of same element with different mass numbers

- Isobars are atoms of different elements with same mass number

- Valency is the combining capacity of an element based on valence electrons

- Electrons fill shells in order: K (2), L (8), M (18), N (32)

- Octet rule: Atoms try to have 8 electrons in outermost shell for stability

- Valence electrons determine how an atom reacts with other atoms

NCERT Notes for Class 9 Science

- Chapter 1 Matter in Our Surroundings Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 2 Is Matter Around Us Pure Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 3 Atoms and Molecules Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 4 Structure of the Atom Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 5 The Fundamental Unit of Life Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 6 Tissues Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 7 Diversity in Living Organisms Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 8 Motion Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 9 Force and Laws of Motion Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 10 Gravitation Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 11 Work, Power And Energy Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 12 Sound Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 13 Why Do we Fall ill Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 14 Natural Resources Class 9 Notes

- Chapter 15 Improvement in Food Resources Class 9 Notes